Tribes, Smoking and the Enlightenment

Thank you for welcoming me to this august group of free-thinkers. The ideas propounded in this blog are important far beyond the specific issue of tobacco use. They address the broader issue of personal sovereignty, of the right of individuals to choose their own thoughts and actions, their own means of personal enjoyment, free from the censure of self-appointed philosopher-kings. I will expand on this line of thinking in subsequent posts, as it relates to the metastasizing influence of cultural Marxism, post-modernism, and political correctness.

So then, please allow me to introduce myself. I’m a man of wealth and taste. Well, taste. Maybe a little.

Prior to my retirement in 2007, I spent seventeen years and six months with a major multinational tobacco corporation, working in the areas of marketing research, analysis, and forecasting. Before that I had worked for the Coca-Cola company until, in 1989, I was “right-sized” out.

That separation had more than just financial or career ramifications for me; the impact was almost existential. I had for seven years been part of a family, or perhaps more accurately a tribe, that was admired and beloved worldwide. When I would inform a fair young maiden of my membership in this tribe, her eyes would often softly widen and her head tilt aside. Thus did come about a number of the romantic conquests of my roaring twenties.

But in 1989, through no fault of my own, I was excommunicated from the Coke Tribe. Purely a business decision, they assured me, nothing personal, as they handed over a decent-sized severance check. While it temporarily bolstered my sense of financial security, it did little to assuage my sense of having been cast adrift. I needed to find a new tribe, and soon.

I got a tip from my first boss at Coke, a man named Suh, a foul-mouthed Korean (is there any other kind?) with a good heart. He knew of a headhunter looking to fill a position with a cigarette company that might be a good fit for me. It paid better than the post I was leaving. And I had no problem with smoking…I was seriously into pipes and cigars at the time. So I took the job.

But this was a different tribe. When informed of my new tribal affiliation, fair young maidens’ eyes went narrow instead of wide, and the sidewise movement of their heads was more a a jerk than a tilt, as if to say, “Why? You seem like a decent guy.” One of them asked me if I had considered the “moral” implications of my chosen position.

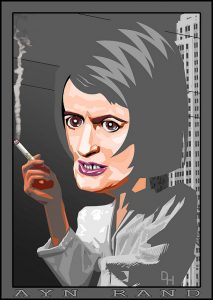

I most certainly had. But we were talking past each other. I’m pretty sure that her view of morality was the standard dictionary definition: “conformity to the rules of right conduct.” Rules as determined by whom? By the philosopher-kings referenced in my opening paragraph? By the sheeple beholden to them and to commonly shared memes bereft of any empirical foundation? To a gauzy standard that exists in the eye of the beholder, convenient to preachers, politicians, and cult leaders, a lazy substitute for the more rigorous philosophical term “ethics?” I hewed to a different view of morality, one inherent in the Enlightenment tradition of classical liberalism, espoused by the likes of Friedrich Hayek, Isabele Patterson, and especially Ayn Rand.

At the core of Rand’s philosophy is that individuals have the moral right, in fact the duty, to make their own choices to maximize their own self-fulfillment, so long as they do not impinge on the free choices of others. She also trenchantly observed that society in general, and government in particular, have an annoying tendency to violate this precept, to impose their strictures on others, seemingly to make sure that no one is enjoying too much success or having too much fun. Above all, she abhorred the collectivist mentality; she glorified individual thought and effort.

Rand was herself a smoker, and had this to say about the practice in her magnum opus, Atlas Shrugged:

“I like to think of fire held in a man’s hand. Fire, a dangerous force, tamed at his fingertips. I often wonder about the hours when a man sits alone, watching the smoke of a cigarette, thinking. I wonder what great things have come from such hours. When a man thinks, there is a spot of fire alive in his mind–and it is proper that he should have the burning point of a cigarette as his one expression.”

Smoking is, for the most part, a solitary and contemplative activity. More on this later.

As we all know, smokers, and the industry that serves them, have come under considerable opprobrium the past three decades. Andrew Lewis, writing for the Ayn Rand Institute in 2000, has hypothesized why this might be:

“…today’s liberals have decided that they can build a more totalitarian government by attacking cigarette companies. By creating a ‘public awareness’ about the dangers of smoking they create the impression that the government is more concerned with your health than you are, thus the need for Medicare and the FDA. By painting the tobacco company executives as manipulative crooks, they create the impression that only the government can control the ‘ruthless greed’ of all businessmen, and so justify the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department. Through legislation and prosecution, they have empowered a generation of litigious, anti-business, anti-conceptual lawyers who will sue anyone for anything. (The lawyers behind the anti-tobacco lawsuits are also behind suits against gun manufacturers and HMOs, to name but two popular targets.)”

But why did the powers that be single out cigarettes for their nefarious plan, as opposed to, say, alcohol? Doesn’t alcohol also wreak havoc on human lives? (and by the way I have no personal animus toward alcohol..a day without whisky is like a day without sunshine). Here is the simple fact: while tobacco products may shorten life, they do not debase it. No one languishes on skid row because he smokes too much. No one has ever been convicted of driving under the influence of nicotine.

I have a theory, based upon the tribalist tendencies to which all of us are prey.

In general, alcohol is more acceptable, more “convivial” in polite society. Alcohol is in fact the drug of choice of the human race. Few if any cultures (tribes) of any era have not consumed it in some form. It is the lynchpin of the Bacchanal, the orgiastic cut-loose in which most tribes occasionally indulge to reaffirm their sense of community and ameliorate, for a time, the dreariness of existence. Alcohol use is for the most part a social activity. It greases the skids of human interaction, and is thus, in this sense, a cultural necessity. The British Admiralty understood this and provided a daily ration of rum to its seamen. The U.S., on the other hand, learned its lesson the hard way with its experiment with Prohibition in the 1920’s, essentially criminalizing an entire nation. After thirteen years of chaos the government of FDR wised up and repealed Prohibition, validating Winston Churchill’s observation that “you can always count on the Americans to do the right thing, after they have exhausted all the other possibilities.”

Tobacco, unlike alcohol, is not a cultural necessity; it is a personal luxury. And, per Rand’s quote above, smoking is a more individual and solitary activity. One of the most successful marketing campaigns of all time was launched in the 1950’s for Marlboro cigarettes. It featured a rugged cowboy riding alone, wild, and free on the open plains (“welcome to Marlboro country”), and it propelled the Marlboro brand to a position of global leadership where it remains to this day.

The concept of the autonomous individual is a modern one, a product of the Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries. Like all concepts, it resides in the cerebral cortex of our brains. The tribal impulse, conversely, is buried in that deeper, older part of our brains that we share with our simian cousins. It is hard-wired and, let’s face it, has ensured the continuation of the species these many thousands of years. Humans were incapable of surviving outside the tribe. Banishment from the tribe was a death sentence.

On the downside, this impulse tends to distrust “others” who are willing to think and act for themselves. Tribalism lends itself to demonizing “others” in order to validate a shared sense of group solidarity, of “us vs. them”, and to signal and affirm one’s membership in good standing in The Tribe.

The Enlightenment led to civilizational advances that were unimaginable a mere three centuries ago. While the Enlightenment has done much to attenuate the tribalist tendency, such deeply imbedded tendencies are not easily swept aside. In fact, the tribalist imperative has over the past century led to wholesale repression of proscribed groups and claimed millions of lives. And over the past three decades, the rise of a post-modernist neo-Puritanism has unchained anew tribalist inclinations to demonize various “others.”

And among these present-day “others” are smokers.

In subsequent posts I will explore various other topics in the War on Tobacco: the frontal assault launched in the 1990’s by various government entities against the tobacco industry, and the industry’s response; the supposed targeting by cigarette companies of under-aged consumers; the supposed artificial spiking of nicotine delivery levels; the ludicrous assertions about the effects of second-hand smoke; and more. Until then, keep the faith.